5G towers: everything you need to know about 5G cell towers

Are 5G towers safe? Has Covid-19 stopped the roll-out of 5G? How do 5G cell towers operate? Here we demystify 5G's most controversial technology.

Get up to speed with 5G, and discover the latest deals, news, and insight!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

5G towers are the key ingredient in getting ultra fast mobile networking into the hands of users around the world, but – despite much of the negative press around 5G dangers – most people aren’t familiar with what the technology on a 5G mast actually does.

According to one survey, 95% of consumers have heard of 5G (although a minority currently own 5G phones). That high level of awareness is testament to strong marketing campaigns from mobile operators, and possibly the high profile debate surrounding Huawei’s role in the country’s infrastructure.

- Discover the best apps for performing a 5G speed test

And of those that have heard of 5G, 55 percent have at least a basic understanding of 5G, while 40 percent are aware of the technical elements of next-generation 5G networks. Despite this general awareness, though, most people have absolutely no idea what technology sits atop the thousands of mobile masts that surround them.

Article continues belowIn this post, we aim to demystify some of the issues around 5G tower technology.

What is a 5G tower?

Masts are essential for the radio layer of a 5G network. In the most simplest of terms, masts transmit data to and from a device to the wider network. They’re often designed to be as discreet as possible, so they blend in with the environment, but there’s only so much that can be done to limit the aesthetic impact.

Indeed, an ill-fated requirement imposed on Orange and T-Mobile in the early 2000s required engineers to plant trees to hide ‘unsightly’ mobile sites. By 2015, network quality was being impacted because no one foresaw that the growth of these trees would block antennas.

If you look around, it won’t be long before you spot a site. The masts used in suburban and rural areas are more obvious – even if some are painted green or brown – but look at rooftops in a city and you’ll see mobile equipment.

Get up to speed with 5G, and discover the latest deals, news, and insight!

In the following video – which we shot on location in Bristol, UK – we took a Mavic Air drone for a flight around the head of a mast, highlighting some of its core components. And with the help of Peter Clarke, a cell technology enthusiast, whose blog goes into extensive detail on 5G and other radio technology, we identified some of the key elements installed on a typical 5G tower.

These sites are either owned and operated by the mobile networks themselves, or through third party infrastructure firms. Each site is connected to the wider network through a fixed or wireless connection known as a backhaul link and hosts antennas that form the radio network.

Operators will use a combination of low, mid and high range spectrum to support different 5G use cases. Some applications will require high bandwidth and constant connectivity, enabled by millimeter Wave (mmWave) frequencies that offer great speeds and capacity. However this is tempered by low range and poor propagation qualities.

This means that in addition to using traditional mobile masts for 5G, operators will need to densify their networks in urban areas, through microinfrastructure such as small cells.

5G towers require new technology

5G will bring ultrafast speeds, greater capacity, and ultra-low latency – characteristics that will allow mobile networks to offer connectivity reliable enough to support critical applications for the first time. This has required a rethink in how mobile networks are built at all three key layers - radio, transport and core. And this has placed a focus on the 5G tower technology that operators are having to install to deliver 5G.

5G networks will be powered by cloud-based cores that allow physical functions to be virtualised and moved around the network. Software upgrades will make it easier to roll out new features, while edge computing will enable ultra-low latency. To deliver this, new technology must be installed on 5G towers.

Upgrade programme for 5G towers

For 5G, operators have been upgrading masts with new equipment that is compatible with their new spectrum. Equipment manufacturers such as Ericsson, Huawei and Nokia have all been working to ensure that their 5G radio gear supports as many functions and standards as possible, while remaining compact and lightweight.

The reasons for this are twofold. The first is that the lighter the equipment, the quicker and easier it is to install. This reduces labour demands and there reduces costs for the operators. The second factor is that because some cell towers will support multiple networks (2G, 3G, 4G and 5G), there is a physical limit to the amount of kit that a site can support. Lightweight, compact, multi-functional equipment reduces demand on space significantly.

Another key 5G tower consideration is the availability of fibre, as there’s no point in having ultrafast radio speeds if the backhaul isn’t there to support it. Operators have supported any measure that promotes investment in fibre networks, but they have been even more vocal about the height of masts.

In parts of Europe, operators are allowed to build masts up to a height of 50 metres. However, UK regulations currently prescribe a maximum elevation of 25 metres (and 20 in protected areas). The taller the mast is, the wider an area it can serve. This reduces the need to build more masts, lowering construction and operational costs (and reducing the number of potential eyesores).

This is particularly important when operators start rolling out the low-range spectrum that will deliver wide 5G coverage. This is especially true when you consider that taller masts would make wireless backhaul a more practical option.

Given the UK government is eager for the country to be a 5G leader, it’s likely that these height rules will be relaxed through revisions of the Electronic Communications Code (ECC).

Microwave 'anyhaul'

A major challenge for mobile network operators has been how to extend existing 4G LTE and 5G connections into areas where a physical, fiber or copper connection to a 5G tower isn’t feasible. One way to do this is to use microwave technology, which can create a point-to-point connection, capable of multi-gigabit speeds.

Microwave anyhaul is a way to transport data to the core network when fiber is not an option. It uses an air-interface to send radio signals (up to 170 GHz), and enables the transmission of data over long distances at ultra-high speeds, whilst supporting network slicing for handling the new demands of 5G.

A recent Nokia trial with Algerian operator Djezzy used Nokia’s Wavence microwave transport product, with an ultra-high capacity of 8.5Gbps, and reaching distances of nearly six kilometers. With its reduced latency and high capacity, the solution will allow Djezzy to deliver new services to its 14.2 million subscribers. And by embracing aggregation, different technologies can be combined to meet the bandwidth demands of an increasingly voracious mobile audience.

And Nokia is also working with a company called BridgeComm, which develops a wireless technology that provides point-to-point data transmission via beams of light, which connect from one telescope to another using low-power, safe, infrared lasers in the terahertz spectrum.

BridgeComm has already integrated some of Nokia's high-speed optical equipment into its systems with successful initial lab demonstrations, which opens the door to a wide variety of applications that commercial and government customers are seeking, such as enabling last mile connectivity in 5G networks and free-space optical (FSO) communication.

Integrated Access Backhaul (IAB)

Elsewhere, Verizon and Ericsson have completed a proof-of-concept trial using new Integrated Access Backhaul (IAB) technology to deliver Verizon’s 5G Ultra Wideband service without the need for fiber installations, relying instead on a dedicated portion of available mmWave bandwidth to connect to the core network.

“Fiber is the ideal connection between our network facilities. It carries a ton of data, is reliable, and has a long roadmap ahead as far as technological advancements," said Bill Stone, Vice President of Planning for Verizon. "It is essential. However, this new IAB technology allows us to deploy 5G service more quickly and then fill in the essential fiber at a later time."

Safaricom, the largest telecom company in Kenya, is another company taking advantage of microwave backhaul, and it has announced that it will be using Aviat's WTM 4800 multi-band radio platform to deliver 5G to its customers.

"We are excited to continue to expand our WTM 4800 multi-band deployments internationally," said Pete Smith, President and CEO, Aviat Networks. "The pace of 5G rollouts is increasing and we plan to leverage our differentiated capabilities to help customers deploy the lowest TCO backhaul possible."

The WTM 4800 is a multi-band product, which combines traditional microwave (6-42 GHz) and E-band (70-80 GHz) over the same link, and same antenna. The benefits of a multi-band installation are lower spectrum costs, as you can offload traffic from costly microwave spectrum onto less expensive E-band spectrum, whilst still maintaining the reliability of microwave technology.

Interleaved Passive Active Antenna (IPAA)

Nokia and Australian telecommunications company, TPG Telecom, recently announced the first global deployment of the latest generation of Nokia’s integrated 5 Interleaved Passive Active Antenna (IPAA) at a TPG Telecom site in Brisbane. This follows the successful introduction of Nokia’s IPAA solution in networks across the world. The Twin Beam version of Nokia’s IPAA delivers both 5G capability and greatly increases the capacity of 3G, 4G and 5G deployed on existing mid band frequencies through advanced antenna technology.

This latest generation of 5G tech not only provides operators the ability to add 5G to an existing site without increasing the number or the size of the existing antennas on the site, but also doubles the range and greatly increases the capacity of all technologies deployed on existing mid band. For example, 1800, 2100 and 2600 MHz frequencies by up to 80%.

And Nokia’s IPAA solution enables operators such as TPG Telecom to upgrade existing sites to 5G by simply replacing their existing antennas with a similar sized unit that supports all legacy technologies, as well as 5G Massive MIMO active antenna, all in a single compact antenna.

Are 5G towers a health risk?

The densification of networks has given ammunition for anti-5G campaigners who seek to block the rollout of masts due to concerns about the environment or on public health. Petitions have been created to oppose the construction of 5G towers in the UK, US and Australia. Campaigners argue that the use of higher band frequencies, as well as the greater numbers of access points, mean 5G is harmful to residents. They are concerned about the electromagnetic characteristics of the technology, the 5G cancer risk, and whether it may contribute to dementia, infertility and autism.

None of these claims are supported by academic studies, and an anti-5G poster has been banned in the UK because it was ‘unscientific’. The World Health Organisation’s (WHO) assessment is that 5G does not present a public health risk.

And in March 2020, it was announced that the International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection (ICNIRP) has deemed 5G to be safe, following a period of extensive research.

The research considered other types of effects, such as the potential development of cancer in the human body as a result of exposure to radio waves.

“We know parts of the community are concerned about the safety of 5G, and we hope the updated guidelines will help put people at ease," said Dr Eric van Rongen, chairman of the International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection (ICNIRP). “We find that the scientific evidence for that is not enough to conclude that indeed there is such an effect,” concluded van Rongen.

The ICNIRP has spent the last seven years working on new guidance for the mobile industry and, while 5G networks were within existing 1998 guidelines, they weren't explcit about high-frequencies above 6GHz.

"They provide protection against all scientifically substantiated adverse health effects due to EMF exposure in the 100 kHz to 300 GHz range," says the ICNIRP.

Clearer regulation for 5G towers

At the recent 5G Realised Summit, Susan Buttsworth, chief operating officer at Three UK, has put forward a number of ways in which the government can help operators deliver 5G, including a reduction in red tape, clearer regulation, and an overhaul of how spectrum is currently allocated.

“We’ve got three examples of how the government can help us more,” Buttsworth explained. “The first one is simply about planning, and consistency between local government and central government. On the one hand, the central government is encouraging us to do things [to roll out 5G networks], and on the other hand local authorities are saying “No, we’re sorry”, and introducing blanket restrictions on certain types of planning.

“And that doesn’t just add time, it adds cost. And if we could simplify that process, but also get consistency between what central and local government wants, that would be hugely beneficial.”

The reticence of local planning departments to approve 5G mast installations and upgrades has also been mirrored in the US, where MNOs claimed that local authorities were not adhering to a 2018 Federal Communications Commission (FCC) declaration, intended to aid the densification of 5G networks, and ensure that cities don't put unnecessary barriers in place.

Safety testing on 5G towers

In the UK the telecoms regulator, Ofcom, has carried out the UK’s first safety tests on 5G base stations and has found no identifiable risks since 5G technology was deployed and that radiation levels are at ‘tiny fractions’ of safe limits.

Measuring 16 5G sites in 10 towns and cities across the UK, the regulator focused on areas where mobile use is likely to be highest. At every site, Ofcom found emissions were a small fraction of the levels included in international guidelines, as set by the International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection. Non-ionizing refers to the type that doesn’t damage DNA and cells. The maximum measured at any site was 1.5% of those levels.

Despite these findings, though, it has been announced that new guidelines will be introduced to increase protection for emerging 5G technology, which operates on higher frequencies. This is significant, as it’s the first time since 1988 that guidelines protecting humans from mobile radiation have been updated. But the new rules won’t apply to 5G phone masts, focusing specifically on 5G phones and devices.

Sadly, none of this news is likely to stop the growing number of protest groups that believe 5G technology is potentially dangerous. And the fact that the research stated that 5G radiation did “slightly heat human body tissue” – although with no evidence of harm – is bound to be used out of context by those people already convinced of 5G dangers.

The growing importance of towers in the 5G era

The advent of 5G will accelerate the infiltration of mobile networks into everyday life and is a strategic priority for governments and operators around the world.

As the construction of 5G networks continues at a rapid pace, the importance of tower infrastructure is growing, a fact reflecting by operator moves to monetise their assets and by rising investments from third parties. Vodafone has moved 62,000 of its towers across Europe into a new company, and plans to launch an IPO in 2021 – potentially netting billions in the process.

5G towers might be considered a blight on the landscape by some, and a health risk to others, but the brave new world of mobile communications won’t be possible without them.

Small cell 5G towers

In towns and cities, the erection of huge masts is an unworkable solution. Even if a local authority consented to such a course of action, the focus on urban connectivity is speed and capacity rather than coverage. Densification is therefore the priority for operators.

5G networks powered by mmWave spectrum will require the deployment of hundreds of 5G small cells, capable of providing the reliable connectivity and ultra-low latency needed for industrial and business applications such as Massive IoT and Virtual Reality (VR).

Small cells vary in size, power and range but are generally compact. Some can even be installed on street furniture such as lampposts, bus shelters and on top of buildings. Because fibre may not be available at all sites, wireless backhaul is a common option and could even be powered by mmWave frequencies themselves in the future.

Planning restrictions are again a common grievance. Operators complain about the absence of a common framework, meaning they have to file a planning application for every single small cell – a time-consuming, laborious task.

There are also accusations that some local authorities are prioritising the direct revenues generated by rental fees over the potential long-term economic and societal benefits that 5G connectivity will bring. This is especially true of smart city applications and the situation is exacerbated by the fact that some councils have given one operator exclusive access to a single operator.

The size of the 5G infrastructure market

According to the California-based company Grand View Research, The global 5G infrastructure market size – valued at $1.9bn in 2019 – is expected to reach $496.6bn by 2027.

5G infrastructure is predominantly made up of a combination of Radio Access Network (RAN), core network, and backhaul and transport, with the backhaul and transport network including fiber optics or microwave antennas. (In terms of value, RAN dominated the 5G infrastructure market with a share of 46.2% in 2019. This is attributable to a robust deployment of 5G RAN with several small cells and macrocell base stations across the globe.)

And as technologies such as mmWave 5G become more widespread, so too does the need for the latest hardware (both at primary cell sites, but also at small cell sites, which we will begin to see more and more in urban areas).

Highlighted findings from the report include:

- RAN technology is estimated to reach a market size of $214.7bn by 2027, expanding at a CAGR of 112.3% from 2020 to 2027, owing to a significant rise in investments for deploying 5G cloud or centralized RAN across key countries such as the US, UK, Japan, and China

- With the growing need to provide unified connectivity across IIoT devices and collaborative robots, the demand for 5G technology and related infrastructure in industrial segment will see considerable growth over the forecast period.

- Huge investments made by infrastructure providers in installing a 5G standalone network to deliver ultra-reliable low latency connectivity for connected vehicle applications is expected to drive market growth over the forecast period.

- The sub-6 GHz segment is expected to account for the largest market size of $302.4bn by 2027, largely attributed to governments focusing on releasing sub-6 GHz frequency bands for high-speed data services across major developed economies.

The conversation around 5G towers, their location, the potential health impact, and the technology housed on them, is only going to intensify. But as 5G phones become more widespread, and the demand for coverage goes up, the public perception around 5G technology is likely to change.

Towercos and the future of 5G towers

Telecom tower companies, usually referred to as 'towercos', are becoming increasingly relevant again, as 5G networks require a raft of new infrastructure to operate. Not only does this mean than mobile network operators need to upgrade, but it also means that investors are keen to spot new opportunities, that can deliver quick returns in the world of 5G stocks.

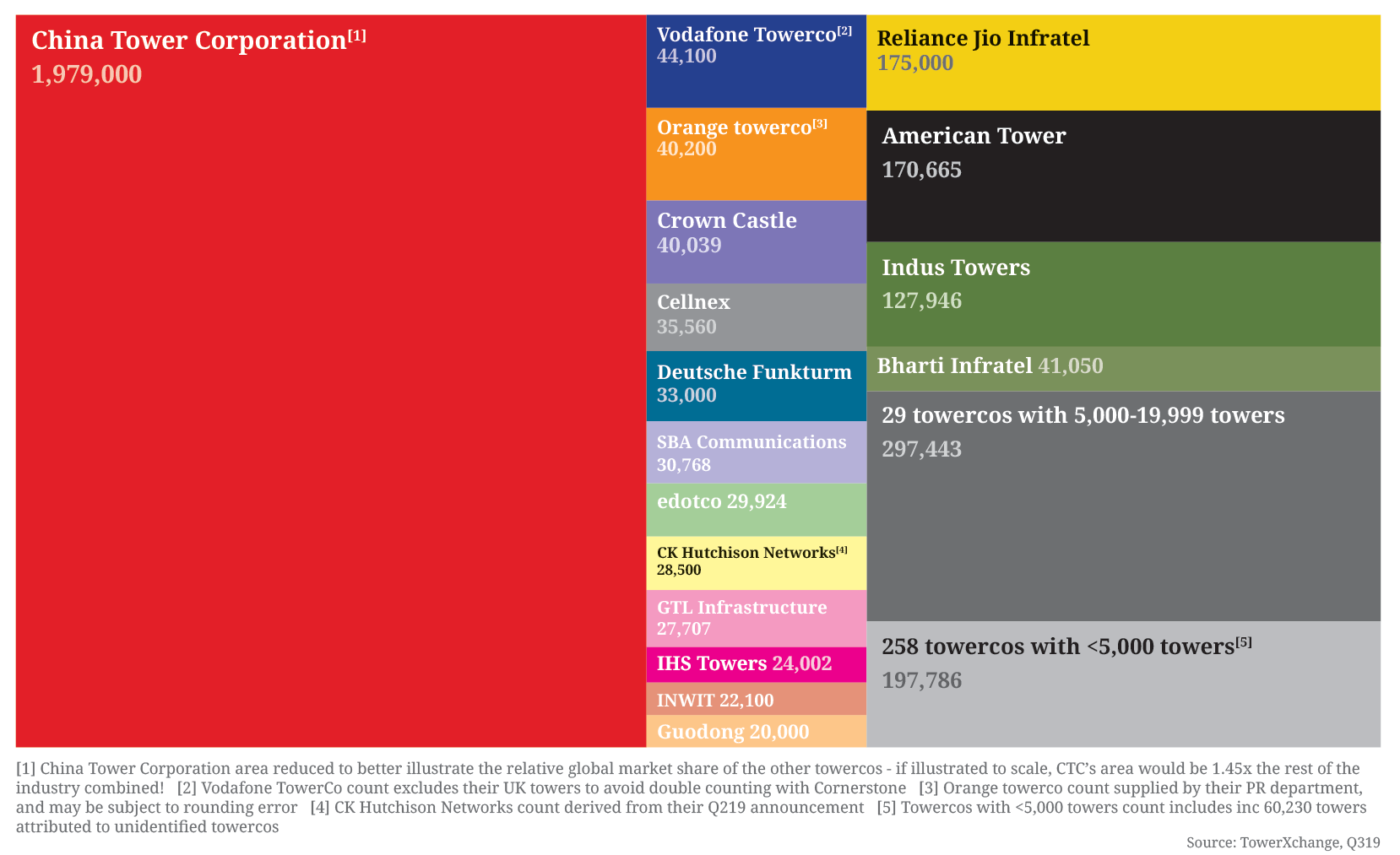

In 2019, a website specilaizing in telecoms towers, TowerXchange, which is an "open community for thought leaders in the emerging market towers industry", looked at the global picture regarding tower ownership, and found that 17 companies around the world were operating 20,000 (or more) towers.

"We had to distort the scale of this infographic to accommodate the massive China Tower Corporation, which represents nearly two thirds of the tower industry’s total towers, while a total of 17 towercos with 20,000 or more towers still represent over 83% of our towers," the TowerXchange report said. "There is still significant scale to be found among the 29 towercos with 5,000 to 19,999 towers, who together own 297,443 towers and rooftops. The tower industry has a ‘long tail’ of 258 mostly privately owned towercos with less than 5,000 sites, which account for 197,786 sites – including 60,230 sites attributed to towercos TowerXchange know exist, but whose names we do not know – the majority of which are from China and Vietnam."

And because all of these towers have the potential to generate income, by allowing other providers to rent a tenancy slot for their own hardware, many network operators are now looking at 5G towers as a potential revenue generator. And the numbers are huge, with TowerXchange saying that 1.45 million towers currently exist as depreciating assets for MNOs, which could be transformed with a shift in strategy.

"Take that same tower, and transfer it to a tower company, and it is transformed into a profit centre: a source of long-term recurring revenue from multiple credit worthy tenants."

TowerXchange.

"Take that same tower, and transfer it to a tower company, and it is transformed into a profit centre: a source of long-term recurring revenue from multiple credit worthy tenants," TowerXchange explains. "The average tenancy ratio of towerco owned and operated towers worldwide is almost exactly 2.0. The capital markets recognise the fundamental differences in the value of tower assets when managed by independent towercos, creating a relative valuation arbitrage between MNOs, with enterprise valuations typically of 4-9x EBITDA, and towercos, typically valued at 9-30x, which drives the continuing transfer of assets from MNOs to towercos."

Put simply: there's a bucket load of money in 5G towers, and the last 12 months has seen companies such as Vodafone looking to exploit this, and apply rent-seeking economics to towers that would otherwise exist only as deprecating assets.

- The best 5G networks in the UK and US

- Why 5G small cells are vital for mmWave 5G

- Millimeter wave: the secret sauce behind 5G

- We reveal the latest 5G use cases

- Discover the truth behind 5G dangers

Steve McCaskill is a former editor of Silicon UK, and is an experienced journalist. Over the last eight years Steve has written about technology, in particular, telecoms, mobile, sports tech, video games and media.